Apocalypse Later

JP Gritton

Dec 11, 2012

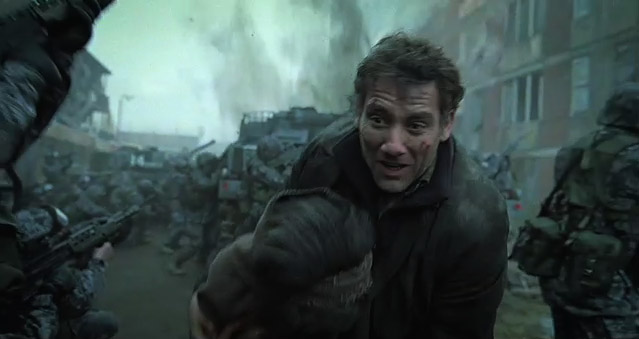

How many times are we going to be promised an apocalypse? How many times are we going to be disappointed? Will I see Mayan death-gods descend from the sky in my lifetime? Are God and Satan ever going to scrap, or did they both chicken out? Maybe as winter approached you found yourself, like me, wondering if the Mayans got it right. Maybe you found yourself making jokes like, "I was supposed to clean my bathroom this week, but it doesn't matter if I clean my bathroom--my bathroom isn't even going to exist after December 21st." And maybe, although you were joking, part of you actually believed that your bathroom would be consumed in an enormous ball of hellfire. The world didn't end on December 21st, and your bathroom still smells. And yet part of you, the part of you that avoids black cats, really thought the world was going to end. At least some of that willingness to believe grew out of the fact that the End of the World has, in recent years, become oddly easy to imagine. Most recently, it started with The Road, Cormac McCarthy's Pulitzer-prize winning novel, later made into a film of the same name. After that, Hollywood generally went buckwild on the theme: from utter horseshit like Seeking a Friend for the End of the World to more arty films like Melancholia and successful ones like Children of Men (also based on a novel, one by PD James), filmmakers are rendering the Apocalypse in sometimes trite but always "compelling" ways. "Compelling" is in quotation marks because that's the operative term, to my mind: I can't tell if these narratives are compelling, or if they have only lately come to seem that way. I'll return to McCarthy's The Road because a) it's a decent book, and b) because it has set a standard for verisimilitude in the genre. McCarthy's End of the World looks and feels a lot like our world: full of cannibalism, rape, murder, fire, canned food. But the strength of the novel's vision lies in its resistance to telling us how the end came about: we hear of ash, of falling snow½so, what? A nuclear war? An asteroid? A climate change thing, or whatever? McCarthy's readers, living in a world that appears to be falling apart at the seams, mentally fill in those gaps he's left us. Because McCarthy resisted the temptation to account for the End of the World, he created a credibly apocalyptic landscape.

"Compelling" is in quotation marks because that's the operative term, to my mind: I can't tell if these narratives are compelling, or if they have only lately come to seem that way. I'll return to McCarthy's The Road because a) it's a decent book, and b) because it has set a standard for verisimilitude in the genre. McCarthy's End of the World looks and feels a lot like our world: full of cannibalism, rape, murder, fire, canned food. But the strength of the novel's vision lies in its resistance to telling us how the end came about: we hear of ash, of falling snow½so, what? A nuclear war? An asteroid? A climate change thing, or whatever? McCarthy's readers, living in a world that appears to be falling apart at the seams, mentally fill in those gaps he's left us. Because McCarthy resisted the temptation to account for the End of the World, he created a credibly apocalyptic landscape.

But here's the rub: the murkiness of McCarthy's success with The Road may suggest a feat at once more tragic and pathetic. On his blog, Peter Y. Paik, a professor of comparative literature at UW-Milwaukee and author of From Utopia to Apocalypse, writes:

But here's the rub: the murkiness of McCarthy's success with The Road may suggest a feat at once more tragic and pathetic. On his blog, Peter Y. Paik, a professor of comparative literature at UW-Milwaukee and author of From Utopia to Apocalypse, writes:

In replying to the question of why apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic narratives have become so popular in American culture in recent years, one may seek the causes in the major events of the past ten years--the newfound sense of vulnerability caused by the attacks of 9/11, the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression, and the destruction which overtook New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.(To Paik's list, I'd add the latest weather-related trauma, Hurricane Sandy.) So December 21st seemed like a plausible (real) end of the world; it seemed that way because it was buttressed by innumerable fictional ends of (fake) worlds; but those fictionalizations arose out of the circumstances of the (real) world itself. For anyone who thinks that life occasionally imitates art, this real-fictive-real resonance is frightening--if we imagine the end of the world, might it not go ahead and end? No, so clean your toilet. As Paik goes on to argue, "the apocalyptic mood of the culture is½not quite commensurate with actual events in the world." Take, for example, the debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan, which don't measure up to what the Athenian navy endured at Sicily; the Great Recession is no Great Depression; Katrina was no Vesuvius; Manhattan flooded, but Rome burned. So why have we shown such a cultural willingness to wax hysterical? I have exactly no original thoughts on this subject, but Paik does:

[T]here is a significant aspect of historical experience that is missing in American culture, which I think goes a substantial distance in accounting for both the mainstream popularity and the hysterical character of our apocalyptic narratives: the experience of being conquered and dominated by a foreign power½.The more ancient a people is, the more memories it has of being subjugated by a foreign other....In most instances, the loss of independence and autonomy becomes a formative aspect of national identity, serving as a decisive rallying point in the constitution of a people.Which may be bad news for American storytellers because, according to Paik, the memory of conquest by a foreign other "grants a people a broader sense of what is possible in the realm of historical experience." Some of these filmmakers'/authors' works are good; many are bad; all of them are hyperbole. Unless you count multinational corporations, Americans have no cultural experience of domination and control by a foreign power (non-Native Americans, at least). And yet in spite or because of this fact, the traumas of the last decade or so have led (some) writers and filmmakers to sublimate a perceived decline in American power--which is not, and should not be confused with, describing the decline of the human species. So, the next time somebody wants you join their cult, or buy some gold, tell them to go away. It's not the end of the world. Yet. Happy New Year, everybody!

Comments (0)

Add a Comment